|

74.

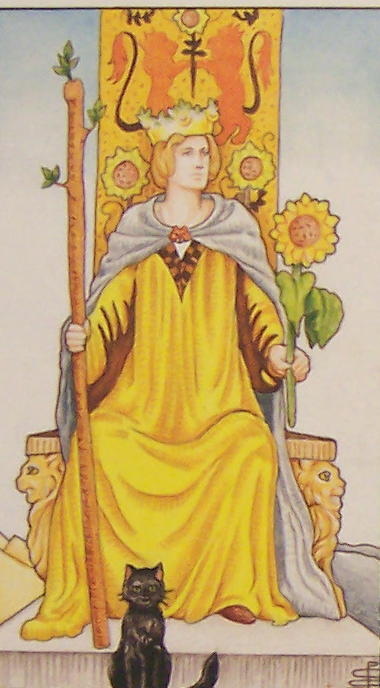

When Filippo finished mixing the cards, Veronica

took the thicker deck and dealt three cards down side by side on the table. "Situations and events," she said. Touching each card with her long

forefinger. "Present, past, future." Now she dealt three cards from the trump deck,

above the three suit cards. "These are the major influences of past and

present"—touching the first two cards— "and this," touching the last card, "is the future. A probable future, I should say.

What is augured. Pronto?" She turned over the suit cards one by one: the

Ace of Swords (past), the King of Coins (present), and the Six of Swords

(future).

"The King is upside down," said Filippo. "Should I right him?"

"No. Leave him alone. Bene, bene, the Ace with

the sword represents the triumphs of your past accomplishments, your

penetrating intellect and what it has achieved. But the reversed King of Coins

shows that you are poor and unappreciated at present."

"Ah, signora, we need no cartomancy for that

revelation."

"Be patient, Filippo. The six is a transition

card, suggesting the need to move forward, but to do so rationally. The two

pip cards are of the same suit, swords, reinforcing each other. In your case

the sword is the intellect. Intellectual battle is very much in the picture,

Filippo, but notice the pips add up to seven, in this context an unlucky

number. Now let's turn over the trumps."

She revealed first the Tower (upside down), then

Temperance, but she left the last trump face down. "Disruptions in the past as a result of your

intellectual battle," she said as Filippo studied the Tower. Two

courtiers falling headlong outside a burning fortress. Or were they rising,

since the card was upside down? "My pedantic Oxford enemies," he suggested. "I vanquished them at The Ash Wednesday

Supper."

"That book had to do with the earth revolving

around the sun, did it not?"

"Yes, you've read it?"

"No. I can tell from this picture. Notice the two

suns in the lower corners. It's really the one sun seen from two different

times of day. The earth is moving and those men are falling off. Their outmoded

philosophy is no longer relevant. But the flames from the burning tower, that's trouble, Filippo, for they point toward the

present and future. More flames, more strife, more battles."

"But Temperance is in the present. A woman who

looks like you, Veronica." The red-haired woman depicted on the card wore

a blue dress studded with yellow stars and moons. She held two pitchers and

seemed to be pouring from one to the other, but the raised pitcher appeared to

be empty.

"She calls for a calm approach, Filippo;

moderation, avoidance of extremes. She is the fourteenth trump, and it has been

fourteen years since I saw you. So you're right, I am Temperance now, telling you also

to be prudent, not to rush into anything, for the flames of the Tower are

following you. But my pitcher is empty. You will not heed my advice." He began to protest, but she interrupted him: "Everything depends on this last card." And she turned it over, revealing il

Bagatto, the Magician, upside down.

As she studied it, frowning and wiping the sweat from

her brow (for the midsummer evening remained warm and muggy), Filippo had

already divined its meaning.

"That has to be me," he said. An artisan at his workbench, with

various tools. A chisel. A pen? Or is that a paintbrush? Filippo pointed. "A wand! He's a magus."

Veronica shook her head. "Mocenigo means you no good, Filippo. Or if he

does now, he will not in the near future."

"Why, because the card is upside down? Couldn't that mean that he will reverse my

present fortune, that he will finally help me win the recognition I deserve?"

"The future is not fixed, Filippo. You may be

right, but all I see is blocked power, ill fortune, deception, trickery.

Remember the Bagatto is the lowest trump. Of high value, but easily

captured. What I see here is this upright woman, whom you have correctly

identified, as being the only thing between you and these flames. Do not accept

the offer. It is a trap."

|