95.

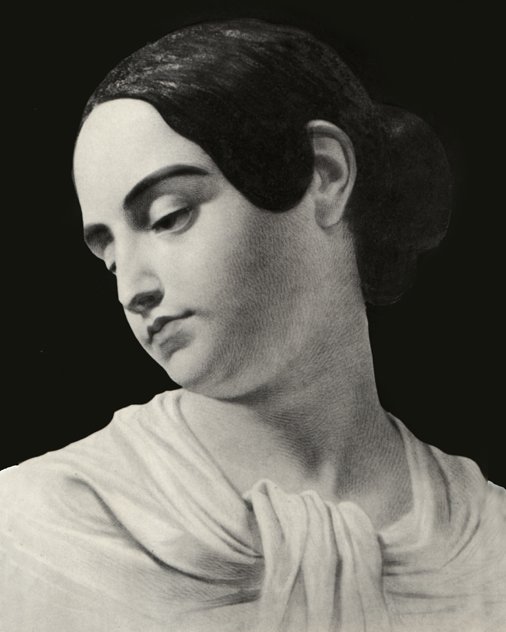

Sissy took something from under her pillow. It was

a small portrait of Eddy, looking young, bright, dashing. She gave it to Loui,

then found in a portfolio also hidden under her pillow an old letter, foxing

yellow, with a brown curved edge where it had started to burn. "It's from Mr. Allan's second wife. Eddy threw it in the fireplace

without opening it. He had just heard that he was left out of Mr. Allan's will." Sissy was losing her breath again. "I . . . saved it from the flames!" She handed it to Eddy. Louisa Allan had not

abandoned him, she had simply ignored him, refused to get to know him, and

never once encouraged his so-called foster father to forgive him for being such

a disappointment. I'm so sorry, Edgar. He now read the words she had written soon

after Allan died. I want to make amends. It was all my fault Mr. Allan never

answered your last letters. I could have softened his heart, but I didn't. A sin of omission for which I wish to atone.

I want to see you. I want to help you. Please write back. That

was thirteen years ago. If he had only read

and answered the letter instead of assuming she was a mere appendage of

her cruel husband; if only he had agreed to see her, she could have

saved him from

abject poverty. His whole life would have been different. Hers too.

"Promise me you'll keep that letter," Sissy said.

"Why? It's too late now. Why didn’t you show it to me

years ago? What good will it do me now?"

"I thought you would’ve been upset with me for

not letting it burn. Please, Eddy, please." She started coughing now, without inhaling,

just gasping and hacking.

"I certainly will keep it, dear Sissy," he said, struggling against unmanly tears as he

put the letter into the portfolio and took it to his desk. "I understand," he said, sobbing and wishing even more for a

drink.

"Everyone thought you a disgrace," said Muddy, "when you got yourself thrown out of West Point.

Mrs. Allan's letter shows that you did not deserve to be

treated that way."

"Darling, darling Muddy," Sissy was struggling even more to speak. "You will console and take care of my poor Eddy—you will never, never leave him? Promise me,

then I can die in peace."

"Where would I go? To Neilson? Don't worry, my child."

Sissy seemed to relax as a serene smile appeared

for a second or so. Then she started gasping for breath, heaving, exhaling

without inhaling.