54.

Would my family

even care that I'm publishing this book? Only Regina, of course. They didn't care about his translations of Swinburne, they

couldn't even read them. That was for the better,

Regina wrote. Paolo thought of her now with such longing for her company, her

unconditional love, her sisterly kisses, wondering if all these womanly

feelings he felt were merely echoes of her soul, phantasms of her body. Admiring

her all my life I wanted to become her? His gaze for a while was lost among

strangers hurrying by on the square, and when he looked back toward the empty

seat next to him he was startled to see it no longer empty. Poe was actually sitting

there.

That's not possible. I'm awake. This is not a dream.

"Good heavens!" said Poe, pointing past Paolo’s shoulder toward

the bustling square. "It's Swinburne! What is he doing in Rome? I thought

Watts had him under lock, key and rod at Pines."

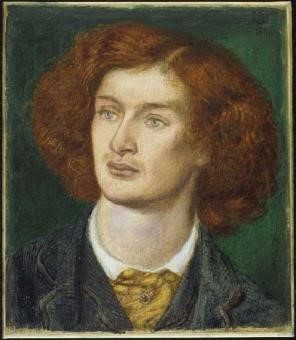

Paolo didn't recognize him at first, that wild bush of

carrot-red hair had thinned and greyed quite a lot since he'd seen him in the bordello. . . .

. . . . Swinburne had told

Signora Lanzetta he only wanted one of her girls who liked to pretend to be a boy. She

was all smiles when she offered him “Paolina.” When Paolo revealed himself as

the very inverse of Swinburne’s request, he expected him to be angry, but

Swinburne was so delighted he gave Paolo more money than he usually earned in a

month. And all the impish poet wanted was frusta frusta frusta culo nudo.

"Please, Paolo," said Poe, "spare me the sordid details. I just cannot brook

Algernon Charles Swinburne. If James thought I was primitive, what must he think of that degenerate lout? Oh

God, he's spotted you. Here he comes. And there I go."

But he’s the

one who first told me I should read you. The chair was empty again. Paolo was still puzzling over whether he

had vanished or had never been there at all, when Swinburne addressed him. "Paolo Paolina! Is that really you?" He sat right in Poe's chair.

"I am flattered that you remember me, Signor

Swinburne."

"As I was flattered by your fine translations of

my ballads." He extended his hand, much pudgier than Paolo

remembered it. "I'm glad I can thank you now in person."

"My Italian colleagues don't share your enthusiasm, signore."

"Indeed? What do such pedants know of our

passions?" He smiled. "So you've gone from puttana to pedagogue. At

least you have moved up in the world, Paolo."

"I enjoy teaching your poems, Signor Swinburne." He felt awkward, even a little stupid next to a

poet he loved to teach, if not always with reverence. "So, what brings you to Rome, signore?"

"I've fled my benevolent captor. One last fling,

that's all I want. And presto! Here you are, my Paolo

Paolina. The goddess is with me today."

"I'm here for the Bruno celebration, the unveiling

of the statue tomorrow."

"Actually so am I. I even wrote a poem for the

occasion."

"Eccellente. May I read it?"