|

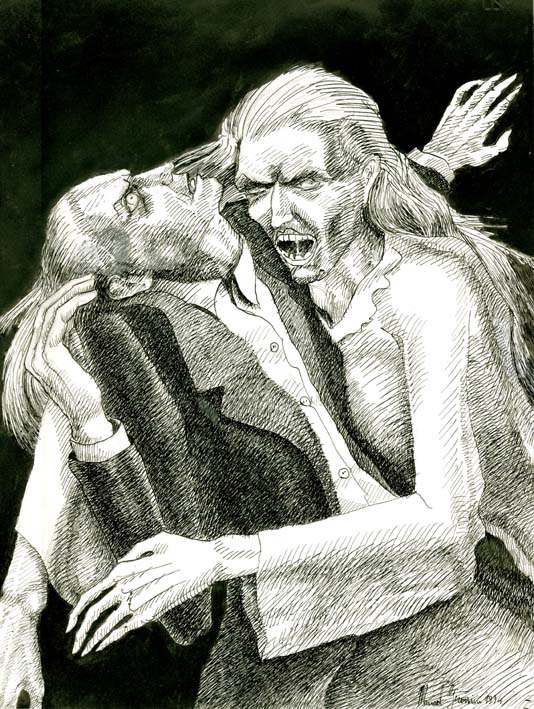

IV. Nature Red in Tooth, Claw,

and Tentacle : Mark Milloff, George Klauba,

and Moby-Dick

Everything

scholarly or critical I’ve written since Immortal

Monster has been, well, on monsters, and on Moby-Dick.

I’d like to end the Last Lecture with excerpts from the

last paper I presented at a conference. It was about two contemporary

artists’ interpretations of Moby-Dick. It is not at all unusual for

modern

artists to become obsessed with Moby-Dick,

painting or sculpting piece after piece until the fever

passes—as Elizabeth Schultz amply

demonstrated in her monumental study Unpainted to the Last: Moby-Dick

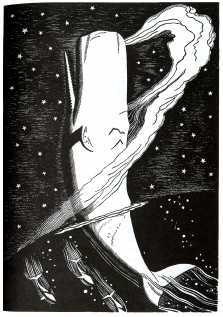

and Twentieth-Century American Art. Here are four examples of

such obsessed artists—Rockwell

Kent, Gilbert Wilson, Robert DelTredici, and my favorite, Vali Myers.

All view Melville's Leviathan in cosmic terms.

Mark

Milloff (whom Schultz discusses) and George Klauba (whom she doesn't) continue the obsessive trend

into the 21st

century. They interpret Moby-Dick in

the context of a question more vexed now than it was in 1851, just

before

Darwin: what is humanity’s “place” in Nature? Are we different in kind from other animals (called

“brutes” in Melville’s day), or are we upright talking apes, omnivorous

bipeds

who slaughter herbivorous quadrupeds, as Melville sees us at the end of

chapter

65, the human animal competing for top predator among all predators?

Milloff

and Klauba, in their rich, overt symbolism--albeit expressed in

completely

different styles--implicitly answer this question. While Milloff

emphasizes the

struggle for survival in a chaotic environment dominated by chance,

waste and

pain . . .

. . . Klauba finds some solace in

the nobility of the individual who reveres

all life, or who has become the victim of human depredation. Both

artists, inspired

by Melville, find continuity between human and animal. And both share

what

Susan Kalter, in her ecocritical article on the novel, has called

Melville’s

“ceto-centric” vision: one that dismantles the Ladder of Being, tips

the Scale

of Nature toward the whale.

When human/animal identities

merge in

literature and art, the result spans a range from the grotesque to the

beautiful. Animal characteristics, especially in Klauba, who produced a

series

of portraits of the novel’s principal characters as birdmen, don’t

necessarily

brutalize or bestialize the human; on the contrary, they may grace the human, adding aquiline dignity

and elegance, but only if the character is noble and sympathetic like Ishmael,

Queequeg, Daggoo, and Tashtego:

In contrast, the obsessed, the

inhumane, those in whom the

inner shark is not “well-governed” by the inner angel (see Fleece’s

sermon), appear

as grotesques. Here, for example, is Fedallah:

Ahab, a bird/squid/human chimera, is also grotesque, but as a tragic figure he's

a bit more complicated than his shadow Fedallah. He’s

noble, but also obsessed, willing to sacrifice others to accomplish his

demonic revenge.

Unlike Klauba, most of

Milloff’s men do

not dominate his pictures—for him, as Schultz points out, the

struggle for survival takes center stage. His wide, crowded canvases

downplay

the individual and the heroic (with the notable exception of Queegueg, below)

as they

represent various species in conflict, competing for dominance in the

sea.

Since the sea is not the environment to which humans have adapted over

the

millennia, they are most often the losers. When butchering whales, they

have to

fight off sharks, even as they contend with the shark within themselves. (“Stripping

the Whale”—notice the teeth on the Pequod’s gunwale.

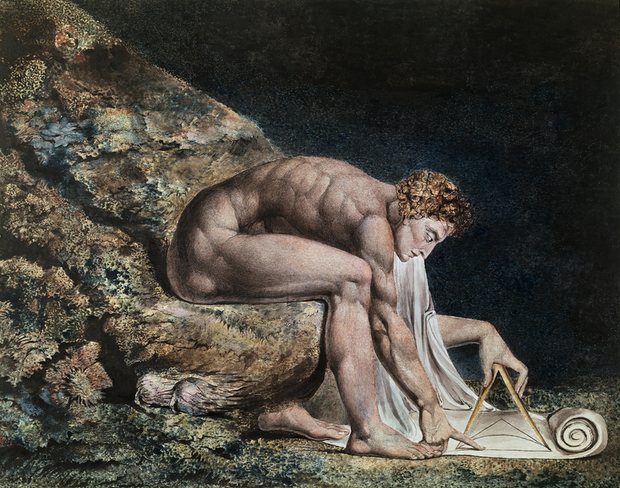

Melville’s theme of human

animality tends

to undercut the notion, long-established in Western culture, that other

animals

are lower than humans on the scale of nature, or Ladder of Being. To

behave

like an animal, according to this cultural meme, is to lower oneself.

And of course the

hierarchic notion tends toward racism: so-called races of color were

assumed to

be lower than white people on the Ladder—closer to animals. Melville

vividly

demonstrates not only that all humans of whatever color equally act

like and as animals, but also that other animals

are not necessarily lower than humans. He denies both racism and

speciesism,

insisting that the whale is the greater being. It is not brute strength

that

enables Moby Dick to destroy Ahab and the Pequod: it is superior

intelligence.

In each of the three climactic chase chapters, the whale outwits his

hunters.

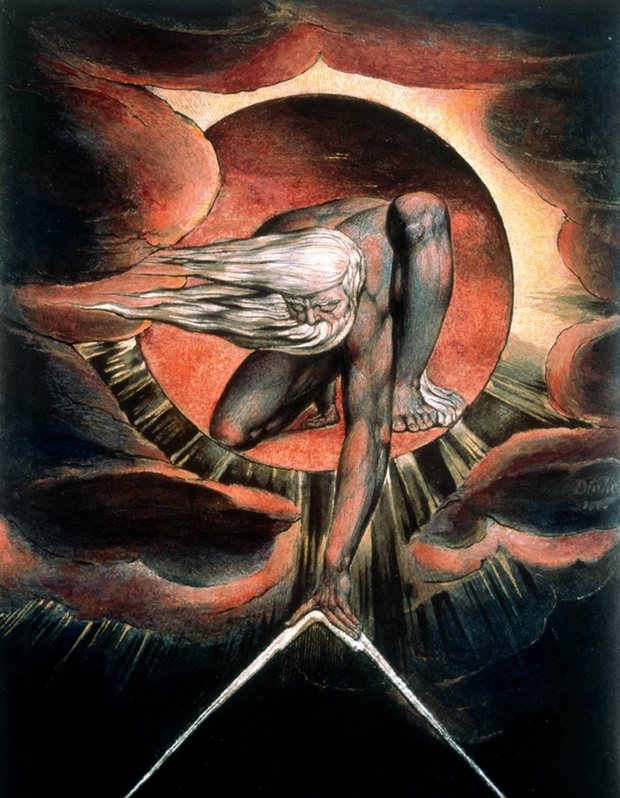

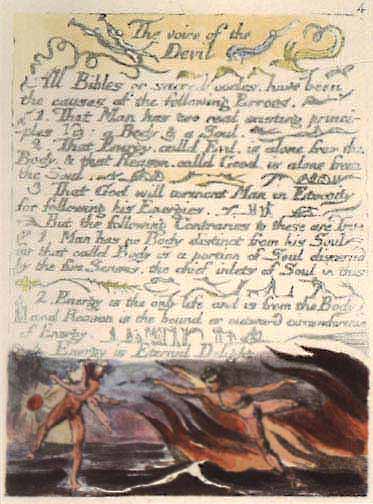

Melville investigates all the

visions and

versions of Nature from the Judeo-Christian view that Nature was

created for

Man’s use, to the Enlightenment Deist notion that Nature provides the

basis for

human morality, to the transcendentalist idealism that has Nature

generated by

spirit—not only God’s, but humanity’s as well, for we are part of God.

But the vision

of Nature most crucial to Moby-Dick as we

read it now is the modern scientific view of Nature as universe to

be

explored, understood, all its creatures studied. When Ishmael presents

himself as

natural historian, he deliberately begins with the unscientific notion,

already

outmoded since 1778, that the whale is a fish. It soon becomes clear

that this

old mis-classification(predating Linnaeus) is the whaleman’s view:

since he

works in a fishery, he catches fish. But then Ishmael lets the whale evolve into a mammal—by the time we get

to the Grand Armada chapter with its “leviathan amours in the deep” and

its

descriptions of nursing mother whales, he has left the fish idea

behind. Not

only are whales mammals, he decides, but they are the most dominant

mammals on

earth. The clash between Ahab’s crew and Moby Dick becomes a clash

between

hunters. The hunted whale is a hunter of squid. All creatures prey on

one

another, whether in “the universal cannibalism of the sea” or the

“horrible

vulturism of earth.”

If we think of the animal as

being both a

metonym and a metaphor, we can make better sense of how the beast is

represented in art. As metonym, it is nearby, it is contiguous to us,

and in

the Darwinian view, continuous with us—we are cousins to the beasts. As

metaphor, the animal stands for some aspect of ourselves. One may argue

that

the metaphorical is only possible because (at least unconsciously) we

recognize kinship, continuity and

contiguity. Before Darwin, animal metaphors were largely degrading; to

call a

man a brute was to insult him. Once evolution is viewed largely as a

blind

process working through natural selection, hierarchy becomes

problematic. At

the very least, it needs to be redefined. Many late nineteenth-century

scientists nonetheless clung to the myths of white supremacy and human

superiority—both of which Melville debunks.

Both Milloff and Klauba

reflect Darwinian

views of Nature, albeit in different ways. I’d like to focus on each

artist’s

illustration of a specific scene in the novel, from “The Chase—Second

Day,”

when Moby Dick rams Ahab’s whaleboat from below, sending it airborne so

that it

“seemed drawn up towards Heaven by

invisible wires,--as arrow-like, shooting perpendicularly from the

sea, the

White Whale dashed its broad forehead against its bottom and sent it,

turning

over and over, into the air; till it fell again—gunwale downwards—and

Ahab and

his men struggled out from under it, like

seals from a sea-side cave” (488--italics added).

Note how the simile likens men to other mammals, the prey

of whales.

This was a carefully crafted attack that involved the whale’s conscious

and

quite successful attempt to tangle up all the boats in their own lines.

He does

this through “untraceable evolutions,” twisting and turning: “. . . the

White

Whale so crossed and recrossed, and in a thousand ways entangled the

slack of

the three lines now fast to him,” that he creates a dangerous chaos of

loose

harpoons and lances that threaten the crew. They have to cut him

free--and

that’s when he dives, preparing to make his torpedo run at Ahab’s boat.

Melville refers to the mess of lines and bristling barbs as “a sight

more

savage than the embattled teeth of sharks.” And when the men are

attempting to

get their boats back in order, they have to fight off the sharks: “ . .

.

little Flask bobbed up and down like an empty vial, twitching his legs

upwards

to escape the dreaded jaws . . . .” (488)

Milloff’s painting, “Drawn

Up towards Heaven by

Invisible Wires” is

one of the last in his Moby-Dick

series (2003).

The

huge pastel on paper (12’ X 8’), certainly captures the chaotic mayhem

caused

by the whale, whose battering ram of a head emerges from the sea, his

lower jaw

painted out of proportion to make the White Whale the fist of the

savage sea.

The distant Pequod sails precariously tilting toward the frame, with

one figure

standing on deck, arms outstretched in alarm. Milloff is

suggesting that all the

other animals in the picture are either in league with the whale or

indifferent to the plight of

the men. Numerous seabirds fly all over the place, reminding us that

only the

men are in danger, for they are out of their element. Ahab’s boat is at

top

center, and he himself hangs on to the airborne boat for dear life,

tangled up

in whale-lines. Ahab is holding his harpoon

uselessly between two fingers, and it is pointed away from

the whale.

The only shark is white belly

up at the

bottom, appearing to be no threat to anyone—he literally pales beneath

the

power of Moby Dick. The men are falling, floating, swimming,

clutching—all the

tools supposed to reflect superior intelligence, the weapons crafted

for

superior hunting, all wrecked or rendered useless. If you look from the

helpless ghostlike figure in the water, then move your gaze across the

scene,

you encounter faces engulfed, disembodied; then you see the glowing,

glowering eye

of the triumphant whale. Milloff shares Melville’s

cetocentric

perspective. The eye of the whale dominates the picture, and the whale

itself

is too grand to be fully depicted.

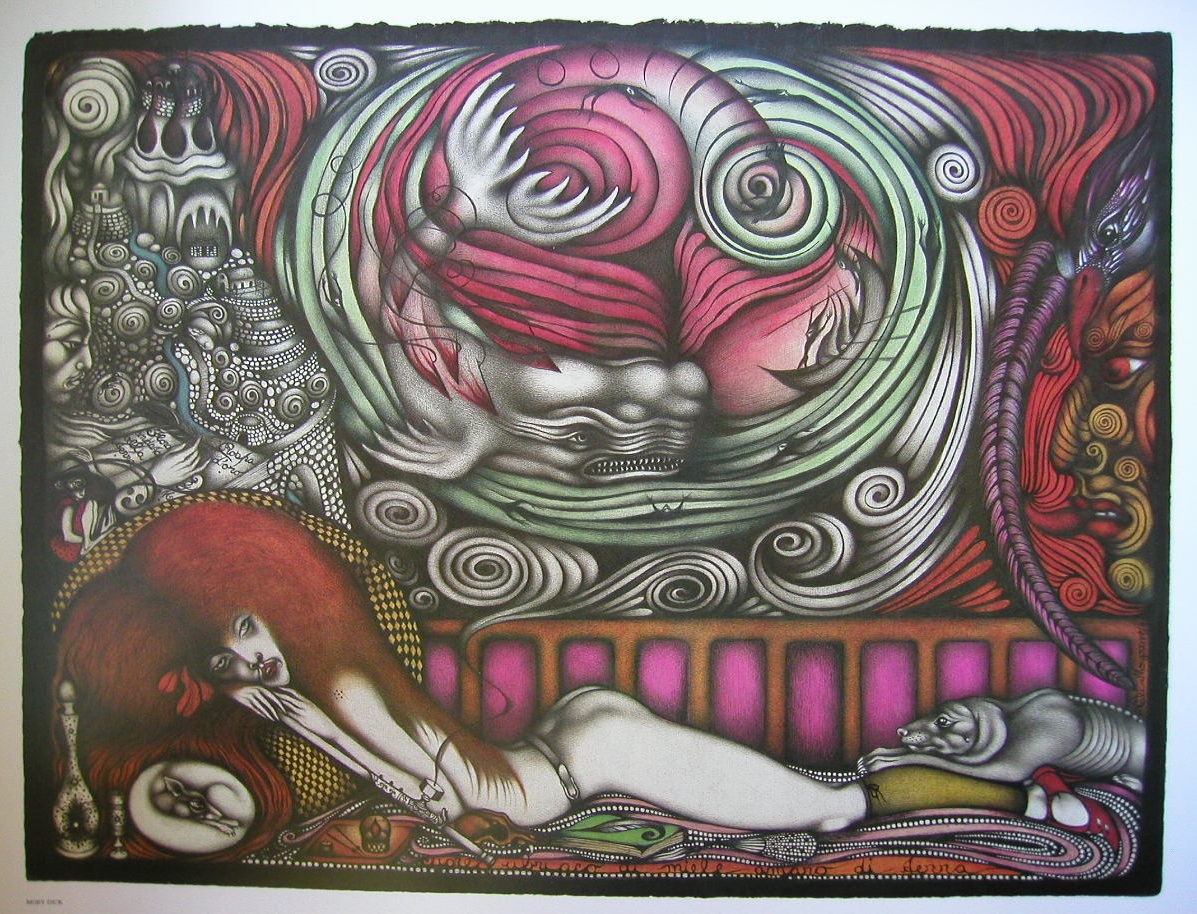

In Klauba’s

version of the passage (2004; acrylic on

panel, 18” X 14.5”), Moby Dick is known only by his impact; he himself

is not

in the picture, but the scene represented is a result of his wrath.

A hole (not

in the novel) gapes in the bottom of the boat, with Ahab falling out of

the

boat, his bird-head not looking so fierce now, but vulnerable as a

baby, his

hand just out of reach of his harpoon. As in Milloff, the oars are

suspended in

the air, useless in this element; the birds soar all around the

tumbling men,

who have lost both hats and harpoons. By keeping the sea off frame,

Klauba

implies that the stricken boat is indeed among the clouds, even higher

than two

of the birds, and situating it diagonally with water streaming from it,

he

suggests an ironic resemblance to a breaching whale. Moby Dick has

indeed just

breached in defiance, before the men lowered their boats. Now a broken

boat

breaches in pale, unwilled imitation and utter defeat. The men may have

the

heads of birds, reminding us of their animal nature, but instead of

outspread

wings they have outspread hands and flailing arms, reminding us, as

does

Milloff, that they do not belong in either sea or sky; they may “seem drawn up towards Heaven,” but they

don’t belong there in either sense of the word, as Ahab made abundantly

clear

when he baptized his harpoon in the name of the devil. He has created

his own

hell, damning and dooming his crew in the process.

Both of these 21st-century

artists seize upon one of the most modern aspects of Moby-Dick,

which they recognize as a key text in the paradigm shift

that would accelerate with Darwin. Humans are part of Nature, not

separate from

it. We participate in the struggle for existence among species. In

Melville’s

sea, we are the invasive species, the whale is our prey. In Milloff, as

he

himself wrote, “Man never wins,” even when he is butchering his prey,

because,

as Klauba also demonstrates in this brilliant depiction of Ahab, he is prey

to his own nature:

On the

whole, Milloff’s vision is more

unrelentingly grotesque, physical and bloody. While some of Klauba’s

portraits

are clearly qrotesques, he seeks out the beautiful and sympathetic.

Even though

he gives us tooth, claw, and tentacle, he also re-envisions the novel’s

spiritual, mystical, and metaphysical power, preserving both the

natural

history and the supernatural mystery of Leviathan.

|

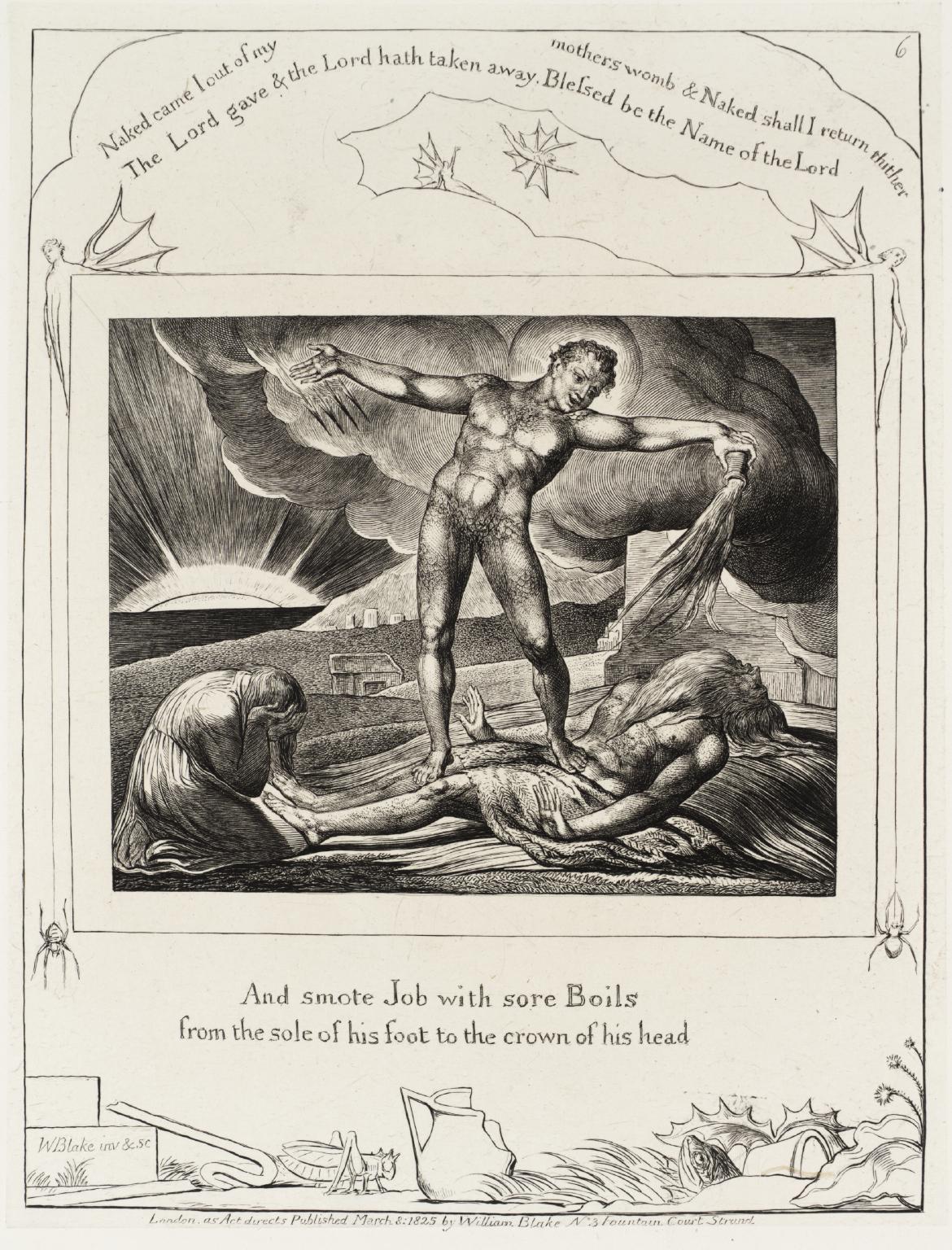

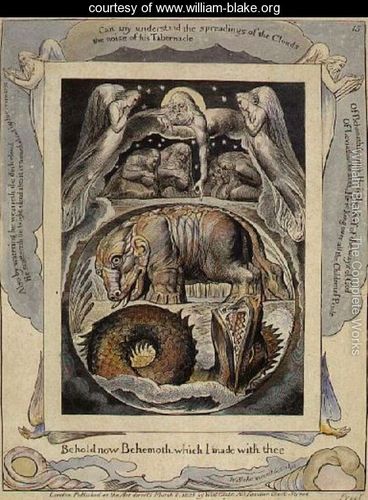

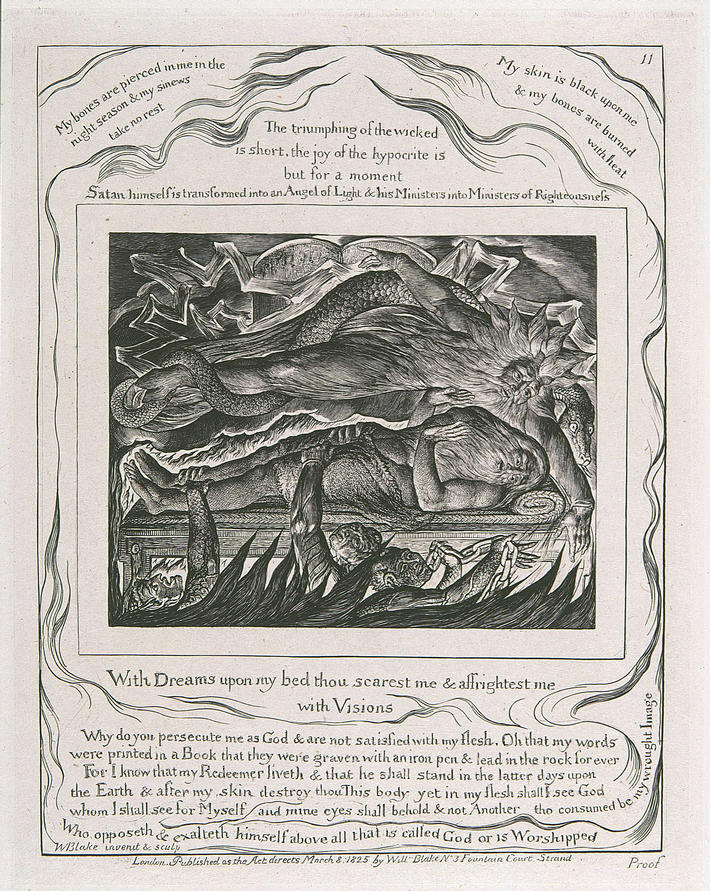

here in Gustave Doré’s 1865 engraving, being

defeated by Jehovah—

here in Gustave Doré’s 1865 engraving, being

defeated by Jehovah—