Another area of research in functional morphology has been on sexual appendages and spermatophores in caridean and penaeoid shrimps. A knowledge of how sperm is transferred to the female and stored there until spawning is of interest both to applied and basic research. In shrimp aquaculture, an understanding of spermatophore transfer is useful in developing techniques of artificial insemination in selective breeding. In basic research on mating strategies, questions are asked such as: can more than one male inseminate a female, resulting in multiple paternity in a single spawning? Do males have adaptations to prevent insemination by other males (paternity assurance devices, such as mating plugs). Please see Chapter 6 in the Bauer, 2023 book for a full treatment of these subjects. The fine 1997 monograph on penaeoid and sergestoid taxonomy by Isabel PérezFarfante and Brian Kensley provides excellent figures of the genitalia of these groups (Pérez Farfante, I. and B. Kensley (1997) Penaeoid and sergestoid shrimps and prawns of the world. Keys and diagnoses for the families and genera. Mémoires du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle 175: 1–233. Below, given as "PF&K, 1997")

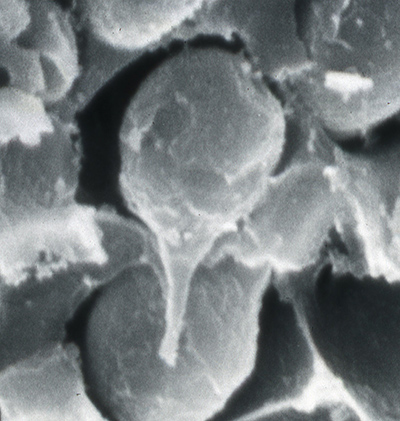

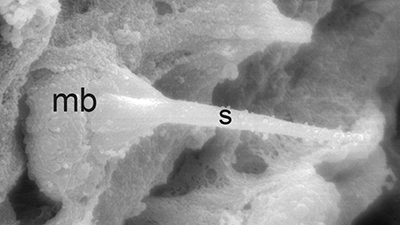

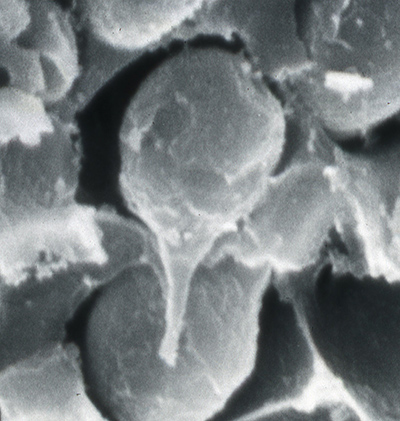

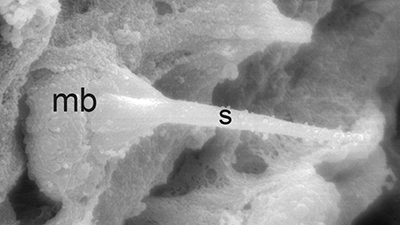

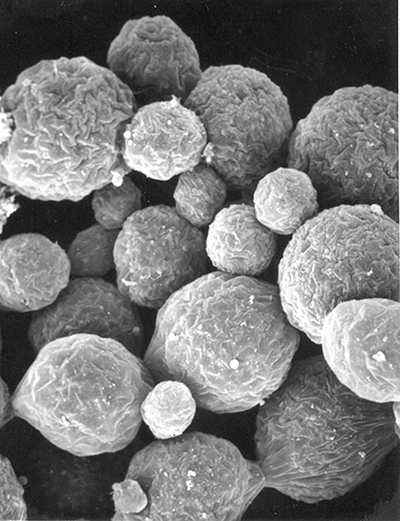

First, some information about sperm in decapod shrimps. As in all decapod crustaceans, sperm cells are immobile. The form of shrimp sperm is quite variable (see the excellent review by Braga et al. 2013)( Braga, A., C.L. Nakayama, L. Poersch and W. Wasielesky, Jr. 2013. Unistellate spermatozoa of decapods: comparative evaluation and evolution of the morphology. Zoomorphology 132: 61–284.) Sperm have a small amount of cytoplasm, a nucleus and acrosomal material. Sperm of many caridean species resemble a thumbtack, with a cap and a spike, but their are many variations. Penaeoid sperm usually have a somewhat globular cap and a spike, while stenopodidean sperm examined are rather flattened cells. Sperm produced by the testes are then packed in various materials to form spermatophores which males will deposit on the female during mating. Fertilization of eggs cells is always external in shrimps.

|

|

|

|

| Sperm cell of penaeoid Farfantepenaeus duorarum | Sperm cell of caridean Lysmata wurdemanni; mb, main body; s, spike (from Bauer and Holt, 1998) | Sperm cell of caridean Rhynchocinetes uritai (from Bauer and Thiel, 2011) | Sperm cell of caridean Thor manningi (from Bauer, 1986) |

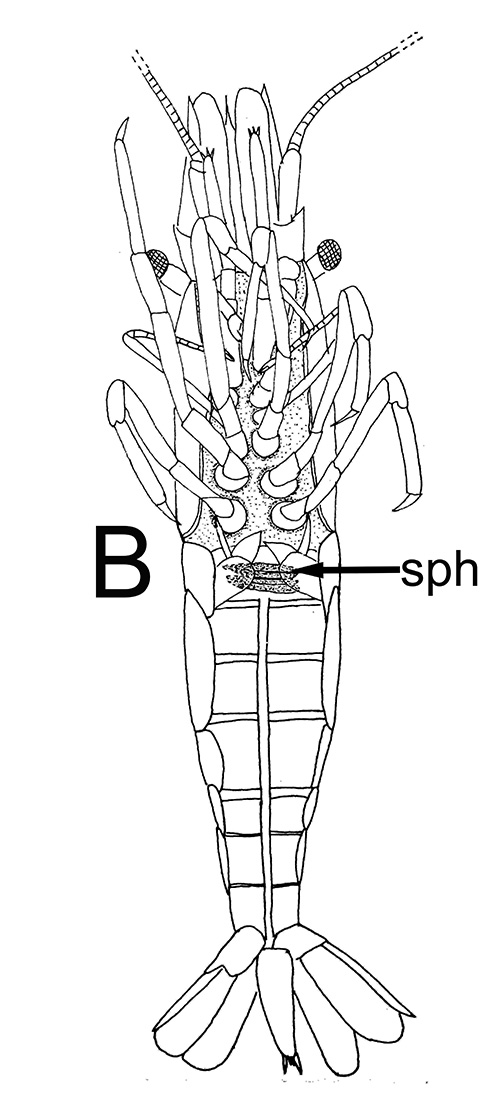

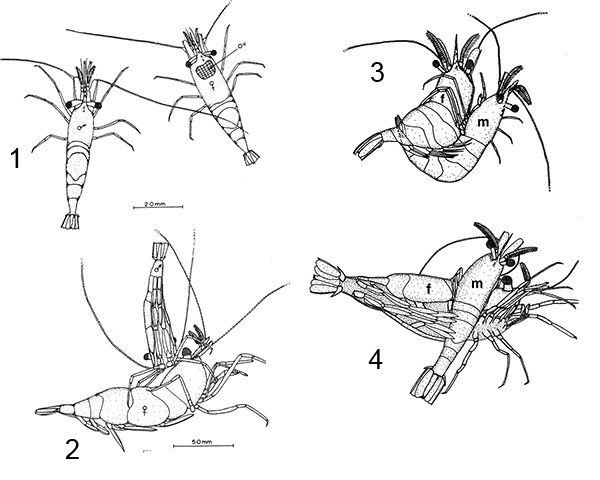

Sperm are packed into spermatophores which are transferred by the male to the female's body during the mating. In carideans and stenopodideans, twin spermatophores formed in the testes and vasa deferentia (sperm ducts), are deposited on the underside of the female, usually between the last two pairs of walking legs on the female's posterior thorax. In at least one shrimp species (Heptacarpus sitchensis), they are deposited on the femailes first abdominal sternite. Spermatophores of carideans and stenopodideans are often simple, with many sperm packed into a gelatinous, adhesive seminal material; in others, they may be somewhat more complex.

|

|

|

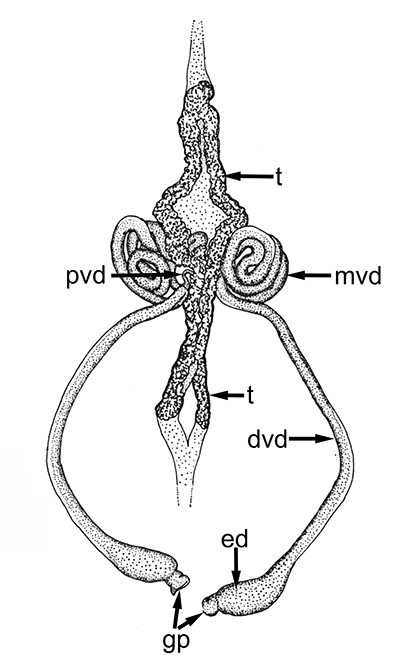

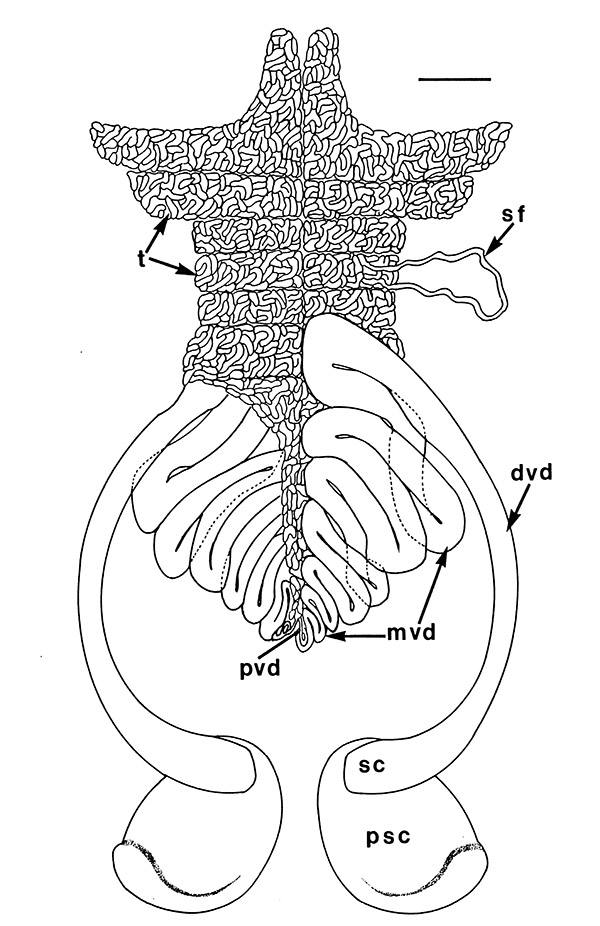

Male gonads of caridean Macrobrachium rosenbergii. ed,, ejaculatory duct; gp, gonopores; mvd, median; pvd, mvd, dvd--proximal, median, distal vasa deferentia (in Bauer, 2023 from Chow, S., Y. Ogasawara, and Y. Taki. 1982. Male reproductive system and fertilization of the palaemonid shrimp Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Sci. Fish. 48: 177-1982.) |

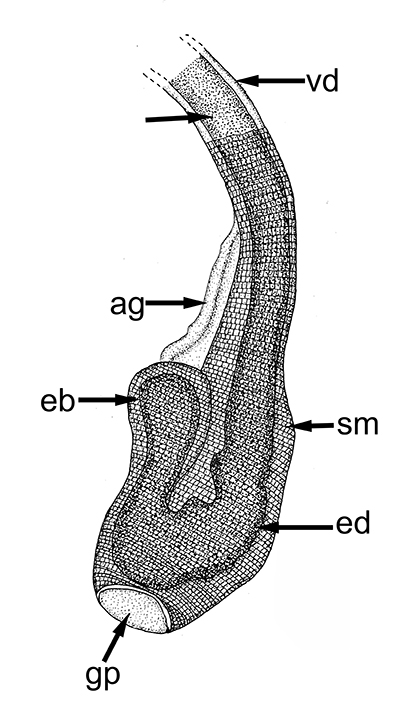

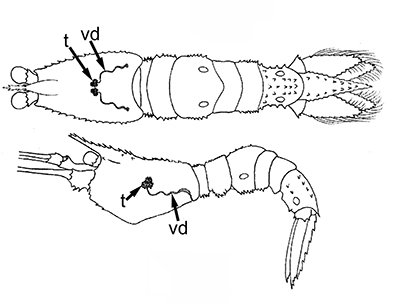

Ejaculatory duct of caridean Heptacarpus sitchensis.ag, androgenic gland; ejaculatory bulb; ed, ejaculatory duct, sm, circular muscle bands that contract during ejaculation to eject a spermatophore mass (from Bauer, 1976) | Stenopus hispidus male gonads. t, testis; vd; vas deferens. The male gonads of this stenopodidean species are quite small relative to those of carideans and penaeoid, sergestoid shrimps. (from Gregati, R.A., V. Fransozo, L.S. López-Greco, M.L. Negreiros-Fransozo, and R. Bauer (2014) Functional morphology of the reproductive system and sperm transfer in Stenopus hispidus (Crustacea: Decapoda: Stenopodidea), and their relation to the mating system. Invertebrate Biology 133(4): 381–393. |

|

|

|

|

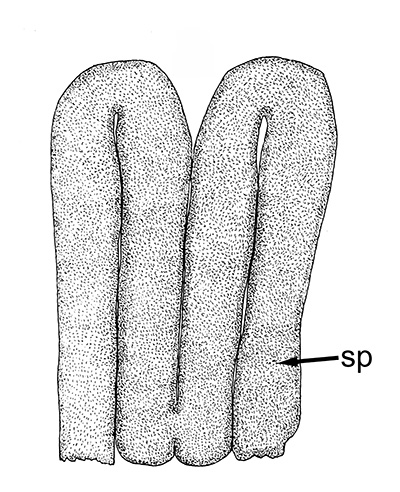

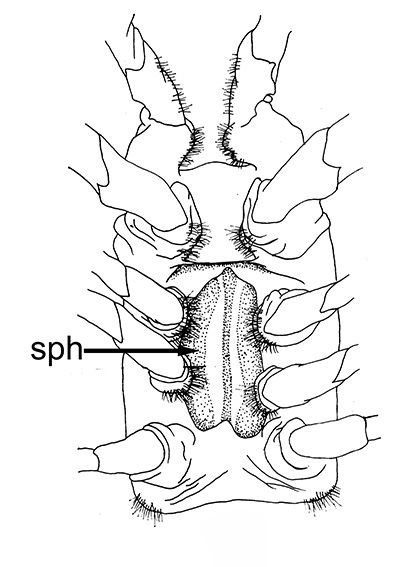

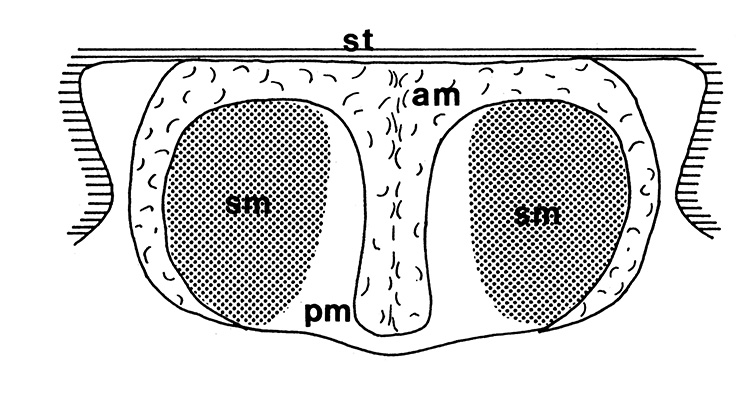

| Twin spermatophores of Heptacarpus sitchensis, abundant sperm (sp) packed within a gelatinous adhesive seminal material (from Bauer, 1976) | Female H. sitchensis with twin spermatophores deposited on the underside of the first abdominal somite after a successful insemination by the male (from Bauer, 1976) | Twin spermatophores on the posterior thorax of a female Macrobrachium rosenbergii (Chow, S., Y. Taki, and Y. Ogasawara. 1989. Homologous functional structure and origin of the spermatophores in six palaemonid shrimps (Decapoda, Caridea). Crustaceana 57: 247-252. | Crossection through twin spermatophores of M. rosenbergii adhering to the underside of a female's thorax. am, adhesive material; pm, protective material, sm, sperm mass. ( 2023 from Chow et al., 1982) |

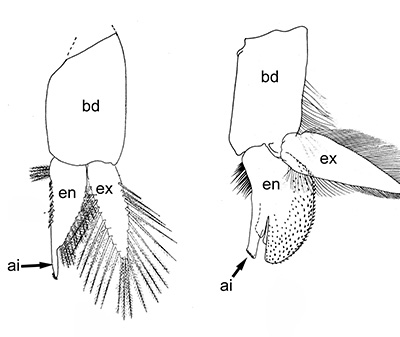

In caridean shrimp, small processes on the swimmerets

(pleopods) of males appear to be important in sperm transfer (Bauer, 1976).

Males of penaeoid species have very complex genitalia, called the petasma. Do these male processes and appendices serve in sperm transfer, stimulate females, species recognition of a mate, attachement to female during mating or some combination of the these?

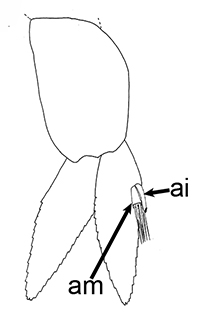

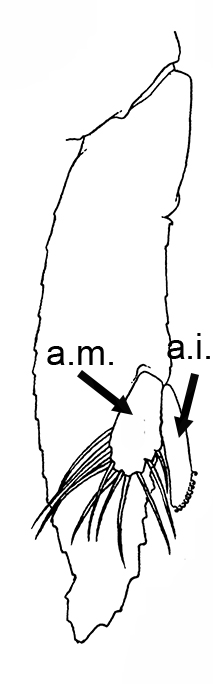

Males of almost all caridean species have a spinous structure of varying complexity, the appendix masculina (AM), on the inner branch (endopod) of the second pleopod (abdominal swimerette). Additionally, males of many species have coupling hooks (cincinnuli), often a stalk (appendix interna, AI) on the endopod of the first pleopod. Like the AI of the other pleopods, the AI hooks the endopods of pleopod 1 together so that they beat in synchrony.

|

|

|

| Appendix masculina (am) on pleopod 2 of Heptacarpus sitchensis; (from Bauer 1976),ai, appendix interna; am, appendix masculina | am and ai on endopod, pleopod 2 of Rhynchocinetes albatrosse (from Chace, F.A., Jr. 1997. The caridean shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda) of the Albatross Philippine Expedition, 1907–1910, Part 7: Families Atyidae, Eugonatonotidae, Rhynchocinetidae, Bathypalaemonellidae, Processidae, and Hippolytidae. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 587: 1–106 ) | First pleopods of Heptacarpus sitchensis (left) and Atya innocous (right) showing appendix interna (ai). bd, basipod; en, endopod, ex, exopod (from Bauer 176 amd r (a) Bauer (1976) and Hobbs, H.H., Jr. and C.W. Hart, Jr. 1982. The shrimp genus Atya (Decapoda: Atyidae). Smithson. Contrib. Zool., No. 364, 143 pp. |

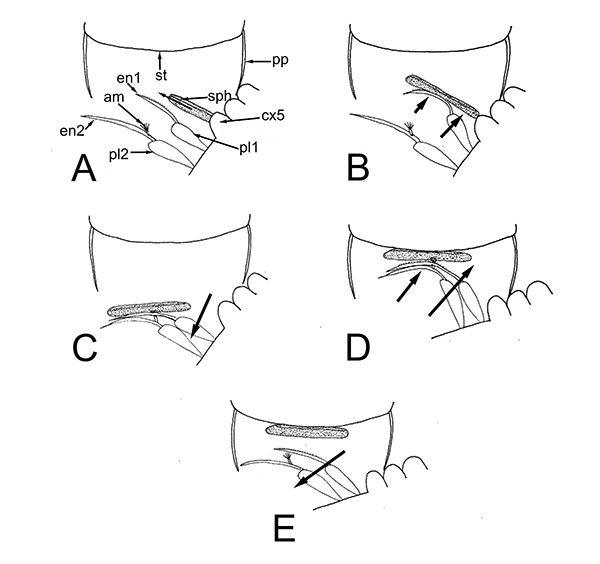

These male pleopods and their appendices are believed to be involved in sperm transfer in many caridean species, as shown with experiments with Heptacarpus sitchensis (Bauer, 1976) and Palaemon (Palaemonetes) pugio (Berg, A.B. and P.A. Sandifer. 1984. Mating behavior of the grass shrimp Palaemonetes pugio Holthuis (Decapod: Caridea). J. Crust. Biol. 4: 417-424). A model of spermatophore transfer is shown below for H. sitchensis

|

|

| Mating sequence in H. sitchensis: 1, male contacts female; 2, male grasps female, climbs on her dorsum; 3, male dips below the female; 4, male in copulatory and spermatophore transfer position (from Bauer, 1976) | Model of how male appendices transfer twin spermatophores to the underside of the female during copulation (A-E shows crossection through female first abdominal somite. am, appendix masculina; cx5, coxal segment of male pereopod 5 which bears the male gonopore; en1,2; endopods of male pleopods 1,2 (p1,p2); pp, pleural plate of female; st, female sternite (from Bauer, 1976) |

The spermatophores, male and female of gonads of penaeoid and sergestoid shrimps are quite diverse and usually much more complex than those of carideans and stenopodideans. Complex spermatophores are produced by correspondingly complicated male gonads. In some species, substances are produced with which the male seals the aperture or apertures to female sperm storage structures ("seminal receptacles," "spermatheca")"

|

|

|

|

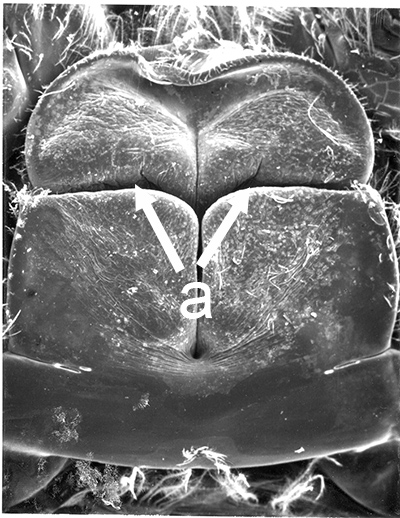

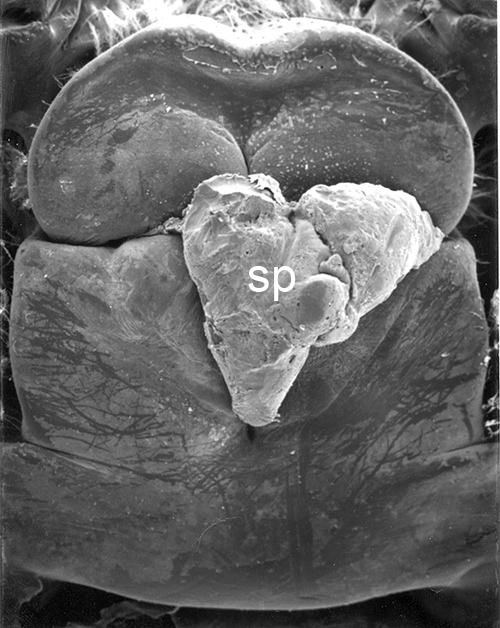

| Male gonads of penaeoid Rimapenaeus similis. Sperm produced by the testes moves through the seminiferous tubules into the proximal, median, and distal vasa deferentia into the sperm chamber of the ejaculatory duct with its gonopore. Sperm are molded in the vas deferentia into globular sperm packets which occupy the spermatophore chamber which opens to the gonopores. pvd, mvd, dvd: proximal, median, distal vas deferens; psc, plug substance chamber; sc, spermatophore chamber; sf, seminferous tubule; t, testis (this and figures to the right from Bauer and Min, 1991) | During copulation ejaculation, sperm packets shown above are inserted into a median chamber of the female thelycum (female genitalia) and then into the paired seminal receptacles inside the female thorax. The male then seals the apertures to the seminal receptacle chamber with the plug substance produced in the ejaculatory duct of the male. The plug substance quickly hardens and prevents other males from inseminating the female until her next mating molt. | External view of the female thelycum on the underside of her posterior thorax. The view above shows an uniseminated female with the apertures (arrows) to the seminal receptacle chamber leading to the seminal receptacles. | Thelycum of an inseminated female with male plug substance (sp) protruding from the seminal receptacle chamber. This hardened material is a "paternity assurance device" which blocks other males from inseminating fhe female until her next molt, at which the cuticular thelycum, seminal receptacles and plug substance will be cast off and replaced with a clean set of genitalia readied for a new mating. |

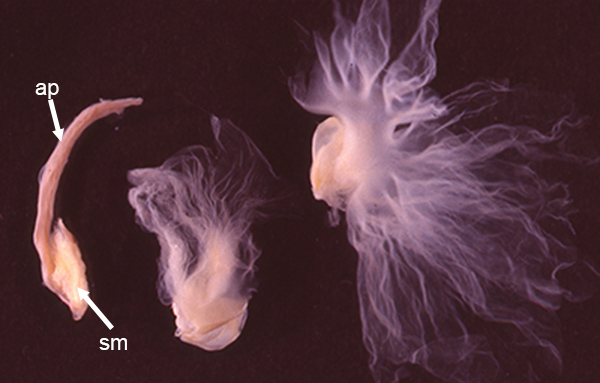

Another example of a paternity assurance device in penaeoids is found In Farfantepenaeus (formerly Penaeus) duorarum, a commercially important of the Gulf of Mexico and southeastern coast of the U.S. During mating, the male inserts twin sperm masses into the female thelycum's median seminal receptacle which is covered externally by twin cuticular plates. A tighly rolled appendage attached to each of the sperm masses unfolds, covers the aperture to the seminal receptacle and hardens, preventing other males from inseminating the female until her next molt.

|

| Sequence of the spermatphore reaction of Farfantepenaeus duorarum (see explanantion above). Far left, newly emitted spermatophore with "appendage" (ap) and sperm mass (sm). The sperm mass is inserted into the seminal receptacle. Upon exposure to seawater, the appendage unfolds and spreads out (middle, far right) to cover and seal the aperture to the seminal receptacle (from Cash and Bauer, 1991) |

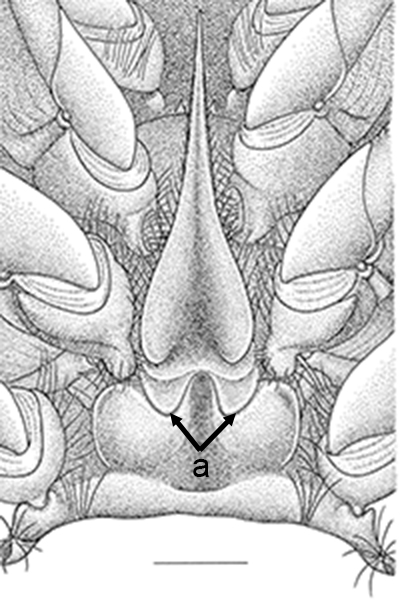

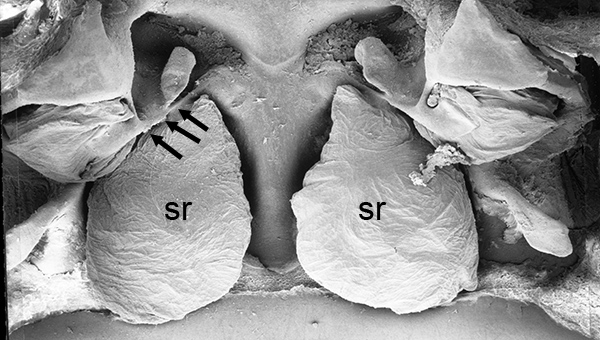

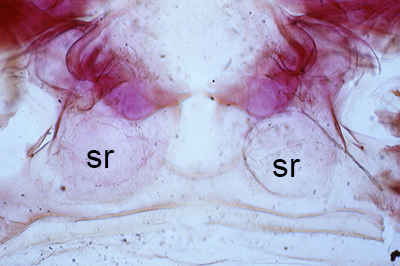

Rimapenaeus and Farfantepenaeus are above are examples of penaeoids with "closed thelyca," i.e., species in which the female thelycum has apertures to a single median (Farfantepenaeus) or more often twin (Rimapenaeus) seminal receptacles. In such penaeoids, the male often seals the apertures to the receptacles with a male secretion (plug). However, in the another closed thelycum group, the "rock shrimps, Sicyonia spp., the apertures are not sealed by the male. The male vasa deferentia do not form any type of plug substance and the spermatophores are simple cords of sperm inserted directing into the female's seminal receptacles. Mating experiments have shown that the lack of male mating plugs allows two or more males to mate with the same female and potentially deposit sperm in the spermathecae of a female (see Bauer, 1992b). The female may allow a male to copulate but not allow insemination. She may allow insemination of one receptacle but not the other, which may be filled by another male. Her offspring may have multiple fathers which has the advantage of genetic diversity of resulting offspring.

|

|

|

|

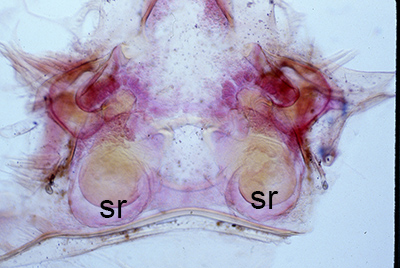

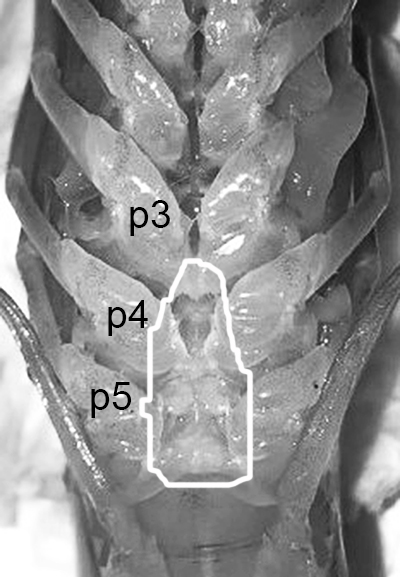

| Thelycum between the posterior female pereopods (walking legs) of Sicyonia edwardsii. Sicyonia spp. have closed thelyca (sperm stored in internalized seminal receptacles) but unlike most other closed-thelyca penaeoids, the apertures (a) to the seminal receptacles are not covered by genital plates or other cuticular structures (from Pérez Farfante, I. (1985). The rock shrimp genus Sicyonia (Crustacea: Decapoda: Penaeoidea) in the Eastern Atlantic. Fishery Bulletin 83: 1–79. | Seminal receptacles (sr) of Sicyonia dorsalis, dorsal view from within the female thorax with other internal organs or structures removed. arrows point to where the apertures of the seminal receptacle open externally. (SEM, R.T. Bauer) | Cuticle of posterior thorax of a recently molted S. dorsalis female, cleared and stained for microscopy, showing empty seminal receptacles (sr). Any sperm that was within the receptacles before molting is cast off with the molt skin. The female will be receptive and attractive to males. (from Bauer, 1992b) | Seminal receptacles (sr) of a recently mated S. dorsalis female, showing filled receptacles. The brownish/yellowish material with the receptacles are sperm masses deposited by the male during mating. (from Bauer, 1992b) |

The examples of penaeoid thelyca given above all referred to as closed-thelycum species. However, many penaeoid species are open-thelycum species, i.e., the spermatophores are deposited externally on the thelycym, not in seminal receptacles. They are exposed to the environment. In closed-thelyca species, mating occurs after the female molt, when her seminal receptacles and thelycum are soft. One to several spawnings occur later using the sperm stored in the seminal receptacles. In open-thelycum species, mating is usually not closely linked to female molting. She becomes receptive and attractive to males when her ovaries are full and ready or nearly ready for spawning. Some examples are given below.

|

|

|

|

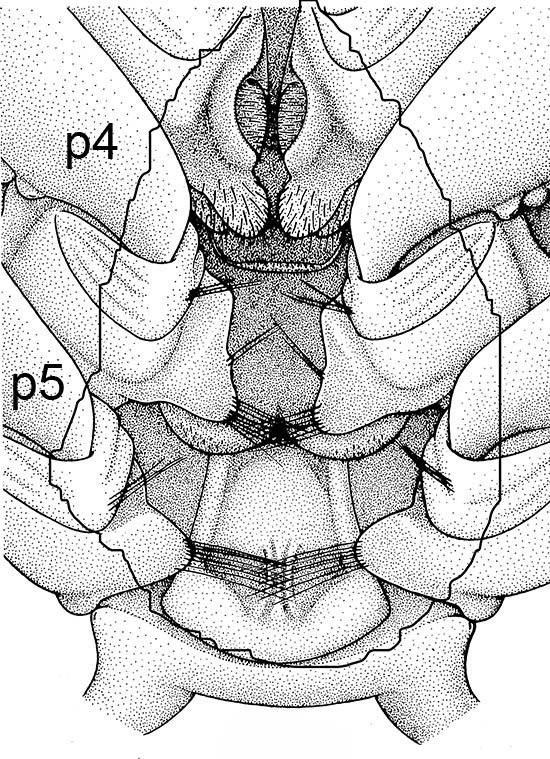

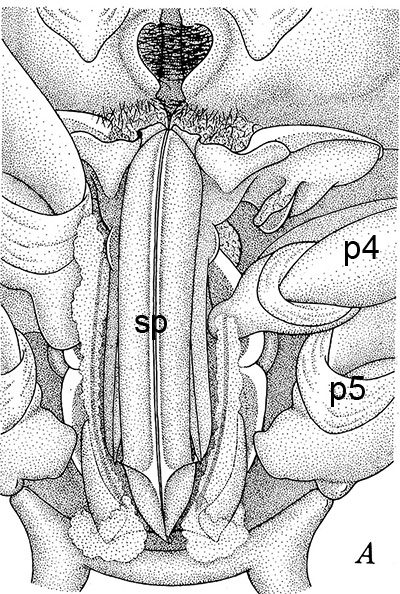

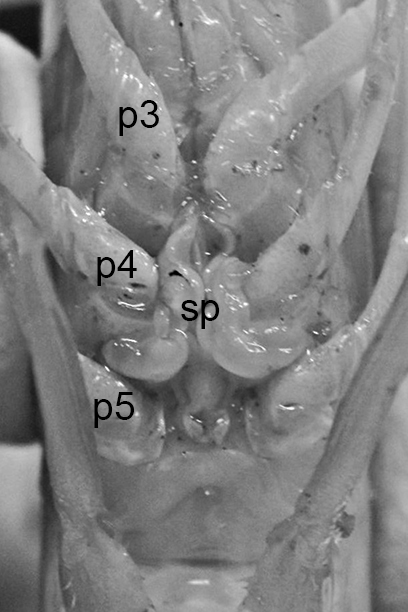

| Penaeid Litopenaeus schmitti,ventral view of posterior thorax, area of open thelycyum outlined (jagged black line) of uninseminated female. p3-5, pereopods 3-5 (from Pérez Farfante, I. (1975) Spermatophores and thelyca of the American white shrimps, genus Penaeus , subgenus Litopenaeus . Fishery Bulletin 73: 463–486. ) | L. schmitti thelycum of inseminated female with complex external twin spermatophores (sp) attached (from Perez Farfante 1975) | Solenocerid penaeoid Solenocera melantho, ventral view, posterior thorax, uninseminated female, open thelycum area outlined in white. Courtesy of Jun Ohtomi | S. melantho ventral thorax of inseminated female, showing twin complex external spermatophores (sp) attached to the open thelycum. Courtesy of Jun Ohtomi |

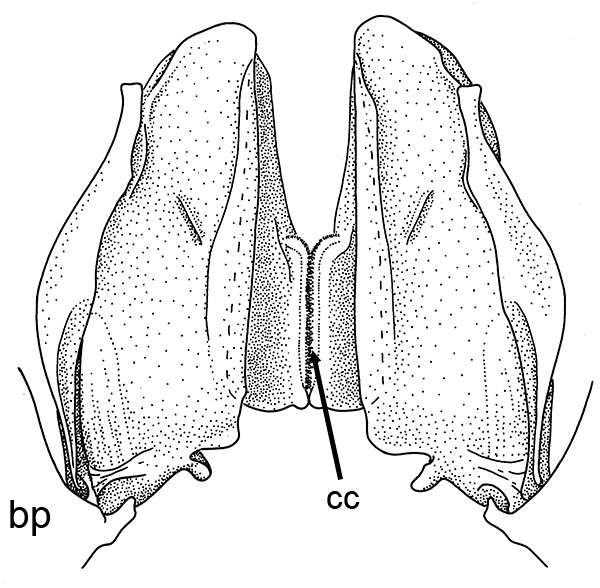

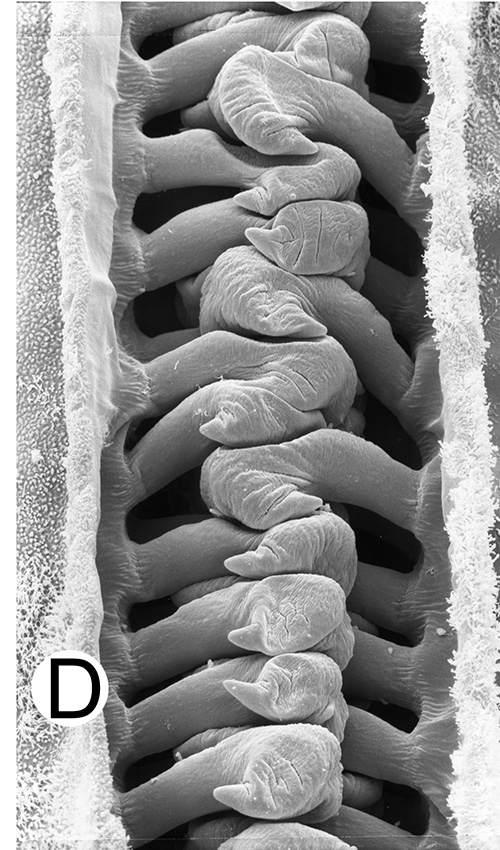

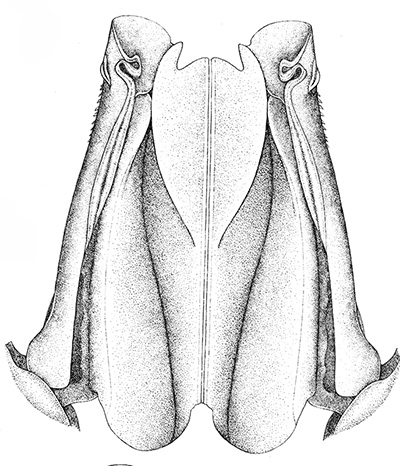

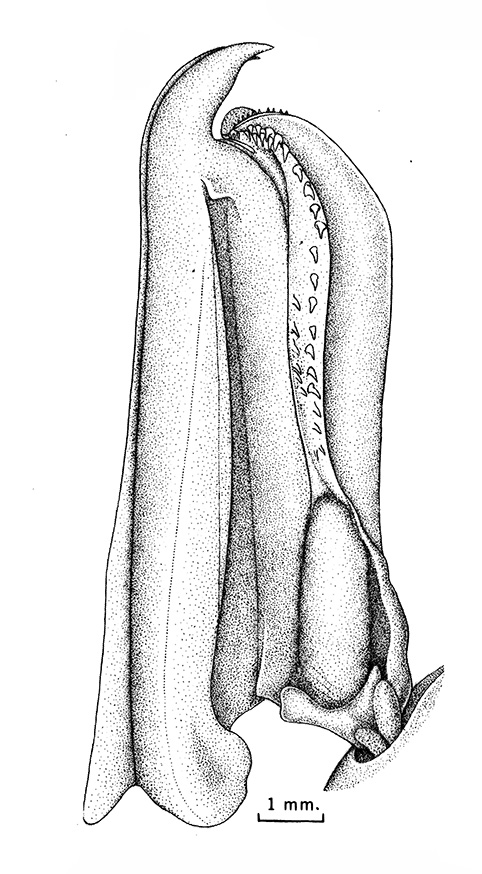

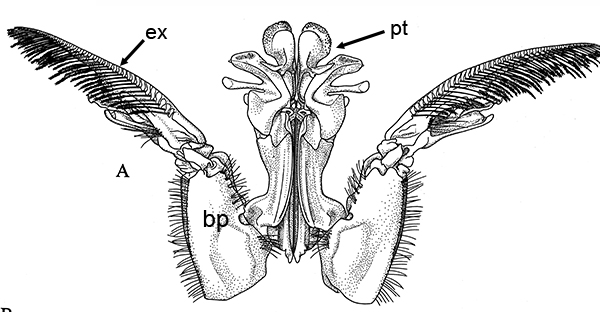

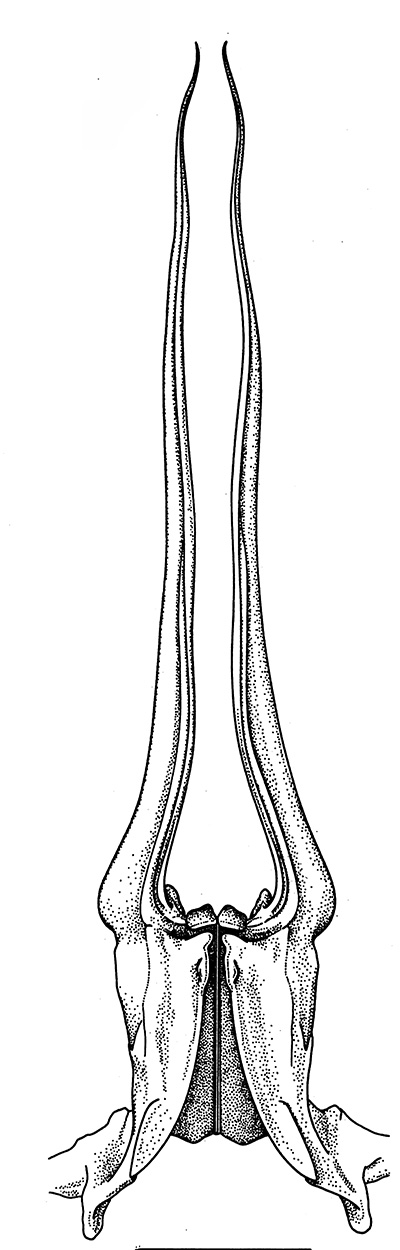

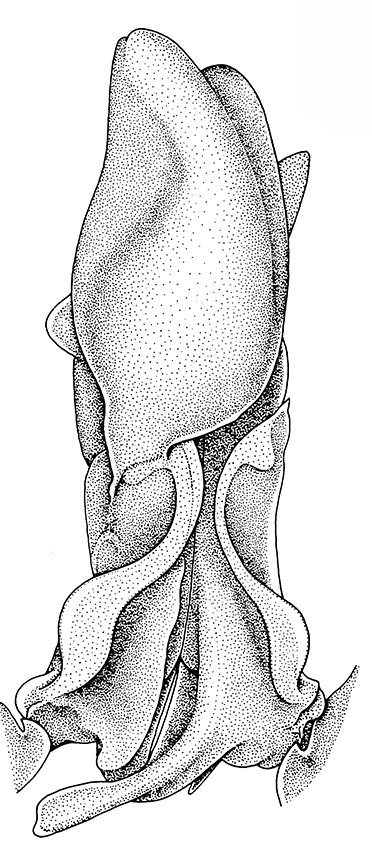

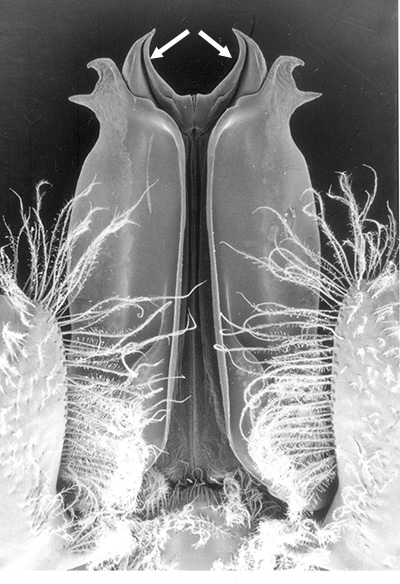

Compared to carideans and stenopodeans, male penaeoids and sergestoids have quite complex, often bizare, genitalia. As in other shrimps the first and second pleopods are involved, especially the first, which I will concentrate on. In these groups the endopods of the first pleopods are linked together by cincinnuli (coupling hooks) to form a structure termed the "petasma." Petasmata may be clasified by somewhat subjective terms such as "open" or "closed. In an open petasma, the endopods are side by side so that twin spermatophores can be placed there to be transferred to the female, as in the aristeid penaeoid and sergestid species shown below. In many others, the endopods can be partially ("semi-open," "semi-closed") flexed ventrally towards each other. In "closed" petasmata, the endopods are completely flexed ventrally to join or almost join; closed petasmata are usually calcified and rigid with limited or no flexibility. The manner in which spermatophores of this type of petasma are transferred to the female is still a matter of conjecture.

|

|

|

|

|

| Open petasma of Aristeus antennatus, ventral (posterior) view. bp, basidpod of pleopod 1; cc, cincinnuli (from PF&K, 1997) | Cincinnuli linking petasmal endopods in penaeoids, sergestids (SEM, R.T. Bauer) | Open thelycum of sergestid Robustosergia robusta (from PK&K, 1997) | Semi-open petasma of penaeid Litopenaeus setiferus, with petasmal endopods spread apart to show ventral (posterior) view; in life and preserved specimens, the ventral lobes are loosely flexed towards each other (similar in apperance to semi-closed petasmata, shown next on the right (from Pérez Farfante, I, 1969. Western Atlantic shrimps of the genus Penaeus . U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv., Fish. Bull. 67:461-591. ) | Semi-closed petasma of penaeid Farfantepenaeus durorarm from lateral view, ventral side to the right. The ventral lobes are flexed towards each other as in a semi-open petasma, but are less flexible (from Perez Farfante, 1969) |

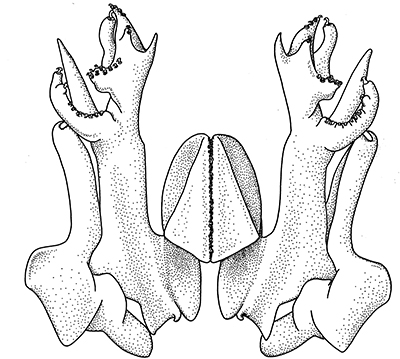

closed: sicyionia, a trachypenaaeus, metapenaeopsis, macropetasma, metapenaeopsis; ideas about sperm transfer;

|

|

|

|

| Pleopods 1 of penaeid Trachypenaeopsis mobilis, showing ventral (posterior view) of the bizarre petasma (pt). bp, basipod and ex, exopod of the pleopod. (From PF&K 1997) | Petasma of penaeid Macropetasma africa, with extremely long extensions of lateral lobes, reaching to the anterior end of the body!! (From PF&K 1997) | A extremely complex and asymmetrical petasma of a penaeid, Metapenaeopsis goodei, with various flaps and lobes (From PF&K 1997) | Totally closed petasma of sicyoniid Sicyonia dorsalis, ventral view, in which lateral lobes are flexed against the dorsal lobes. The petasma is highly calcified and rigid. Arrows show distal "spouts" (arrows) through which sperm material flowing through the interior of the petasma might be inserted in to the apertures of the female seminal receptacles, a hypothesis not yet verified (see Bauer 1996 for alternate hypothesis) |

What does the male petasma of penaeoids and sergestoids actually do in spermatophore transfer and insemination of the female? Some hypotheses that have been proposed or suggested by experimental work of various researchers (see Chap. 6 in Bauer, 2023)

1. Species recognition (female thelycum lock; male petasma key devices)

2. Courtship devices (stimulate female; female choice of superior male)

3. Closed petasma with terminal spouts, closed thelycum spp: Injection devices for sperm transfer into seminal receptacles

4. In some species, petasma may serve simply for attachment to female genital area, with male genital papillae inserted directly into female seminal receptacle(s) (closed-thelycum species) OR onto an open thelycum in other species.

5. Semi-open or open petasmata, open thelycum spp.: spematophores are inserted into the petasma which is presed against the female open thelycum and attached.

This is an area that needs more investigation and especially experimental work with appropriate species.

Spermatophore transfer in stenopodideans, in which females and males have relatively little morphological modification for spermatophore transfer and attachment to the female, is little known but may be uncomplicated. The male may simply squirt seminal material with sperm from genital papillae projecting from gonopores onto the underside of the female during copulation with little or no involvement of the male pleopods (see Gregati, R.A., V. Fransozo, L.S. López-Greco, M.L. Negreiros-Fransozo, and R. Bauer (2014) Functional morphology of the reproductive system and sperm transfer in Stenopus hispidus (Crustacea: Decapoda: Stenopodidea), and their relation to the mating system. Invertebrate Biology 133(4): 381–393 ). Work on more species needed!!

Back to Home Page