More details about corals

There are several different groups of invertebrate animals that are commonly referred to as corals. All of these animals are classified in the Phylum Cnidaria (learn more about classification of Cnidarians at the Tree of Life Web Project or UCMP). The organisms most people think of when they hear “coral” – the shallow-water, reef-building stony corals – belong to the Class Anthozoa. This class is divided into two subgroups: the Octocorallia – so named because they have 8 tentacles around the mouth – include sea fans, sea pens and soft corals; the Hexacorallia - with multiples of 6 tentacles around the mouth - include stony corals, black corals, sea anemones, and others. Another cnidarian class – the Hydrozoa – includes a group of species known as “hydrocorals” (which includes the “fire corals”) because they have a skeleton composed of calcium carbonate, similar to that of stony corals.

Most corals are colonial

Regardless of what group they belong to, most coral species are “colonial” (of course there are exceptions to everything, and there are some “solitary” corals). A colonial animal is one in which individuals undergo asexual reproduction (in this case meaning reproduction without using sperm and eggs), and the newly-produced individuals (called “polyps” or “zooids”) remain attached to the “parent,” even sharing a link between their “stomachs” (called “gastrovascular cavities” in corals). Imagine if you produced offspring that remained permanently attached to you, and anything either of you ate could be shared through tubes connecting your stomachs… then you’d have a body plan similar to a colonial animal!

Most corals have some form of skeleton

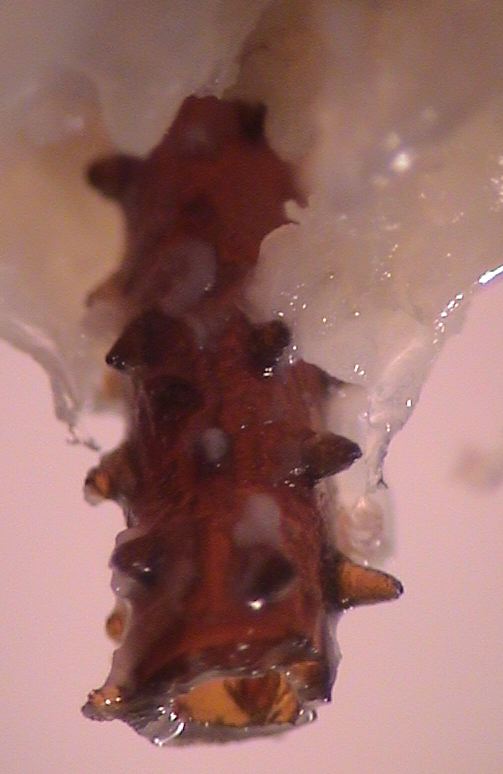

Stony corals (Scleractinia) are so named because they produce massive skeletons made of calcium carbonate. These skeletons are actually external to the tissues of the animal. Basically, an outer layer of cells deposits the calcium carbonate skeleton underneath the colony, so that essentially the colony is sitting on top of its skeleton. Black corals (Antipatharia) grow in a similar way, except that their skeleton is composed of protein, not calcium carbonate, and so is quite flexible and bends in the water currents. Black corals look like plants in that their colonies grow in tree-like, bush-like, or whip-like forms. Black corals are named black corals because their skeletons are black; their tissue may be white or orange or brown (but never black!). Their skeletons are also have small spines, or thorns, and so they are sometimes called “thorny corals.”

The original "coral" was an octocoral

Did you know the word “coral” dates back to the 14th century and was derived from an octocoral, not a stony coral? Specifically, “coral” comes from Corallium rubrum, the scientific name of the precious red octocoral that lives in the Mediterranean and has been harvested for centuries to make jewelry. Octocorals are fundamentally different from stony corals and black corals. They have internal skeletons, their tissues are packed with microskeletal elements called “sclerites,” the polyps have tentacles that are pinnate (which means they have short side branches, like a feather), and they are all colonial*. Octocorals are also often referred to as “soft corals” to indicate that they lack a “stony” skeleton, but among octocoral biologists the term “soft coral” is reserved for a specific group (the Alcyoniina) of fleshy species that lack any skeleton. In fact, one type of octocoral - the blue coral Heliopora coerulea - has a massive calcium carbonate skeleton like stony corals. However, most species have a skeleton comprised mostly of protein (called “gorgonin”), and grow in tree-like, shrub-like or whip-like shapes (the so-called gorgonian sea fans and sea whips).

Our research is focused on the following deep-sea octocoral families – Isididae (the bamboo corals), Chrysogorgiidae, Primnoidae, Paramuriceidae and Acanthogorgiidae - and black corals. Click on the links at left under "Research Areas" for more information on each group. You can learn more about deep-sea stony corals at Lophelia.org.

Want even more detail on octocoral morphology? Check out these sites:

• Octocoral Research Center

•

Shallow Octocorals of the South Atlantic Bight

A relatively common deep-sea octocoral species is Metallogorgia melanotrichos, which we refer to as the "pink parasol coral," seen here on xxx Seamount at xxx meters depth. The colony stands about a meter tall. (Image copyright of the Mountains in the Sea Research Team; IFE; and NOAA)

A close-up of a deep-sea octocoral (Isidella sp.) shows many polyps extended, each with eight pinnate tentacles that surround the "mouth," a characteristic of octocorals. (Image copyright of the Deep Atlantic Stepping Stones Research Team; IFE-URI; and NOAA)

A close-up of three polyps of a deep-sea black coral shows each polyp has six tentacles (seen best in the polyp in the middle; you can also see the "mouth," the narrow slit surrounded by the tentacles) characteristic of hexacorals.

This close-up of a Paramuricea octocoral colony growing at 1900 meters depth shows an example of the many interconnected polyps that characterize a colonial animal. Each individual polyp has a "mouth" surrounded by a ring of 8 tentacles. The 3 large white objects at the top center are barnacles that have settled on the coral. If you look closely you can see the "legs" (cirri) of the barnacle extending from the shell. (Image copyright of the Deep Atlantic Stepping Stones Research Team; IFE-URI; and NOAA)

Black coral skeletons. Left: A branch of Leiopathes shows the black-colored skeleton through a thin layer of tissue; the colorful polyps are arranged on one side of the branch. Right: Stripping away the tissue from a branch of Bathypathes sp. reveals the thorny proteinaceous skeleton beneath.

In this photo showing the manipulator arm of the ROV Hercules about to sample a branch from a deep-sea bamboo coral (Keratoisis sp.) on Bear Seamount at 1478 meters depth, you can see the exposed internal skeleton (bright white with black stripes, below the arm) where tissue has been removed, probably by a predatory seastar. On the still living parts of the colony, the polyps and tissue give the coral a pink hue. (Image copyright of the Mountains in the Sea Research Team; IFE; and NOAA)

A portion of a branch - shown above being sampled - from Keratoisis sp. with the tissue removed to show the internal skeleton. In bamboo corals (family Isididae), the skeleton is comprised of a series of hard calcium carbonate internodes (the bright white parts) separated by more flexible proteinaceous nodes (the dark bands). (Image copyright of the Mountains in the Sea Research Team; IFE; and NOAA)