87.

At the end of the voyage Paolo had to abandon

the cat again, knowing now full well she would find him. He left her hiding in

his berth, where she had remained for days, sneaking out occasionally to do her

business, God knew where. For she acted like a normal cat now that she was with

him again, accepting his leftovers, defecating in the sink when she couldn't get out, demanding his caresses as rewards for

not just shitting at random. Perhaps not

totally normal, for she seemed to know she needed to be quiet, meowing only in

little trills and plurps, staying under pillow and cover when the American was

around. With such help, Paolo managed, in the remaining four days of the

voyage, to keep her hidden from the American, a feat made possible both by his

addiction to cards with genteel female company and by his growing suspicion

(Paolo could see it in his eyes) that Paolo was, if not a little queer, then

certainly rather strange.

A stranger now, indeed, in a very strange land.

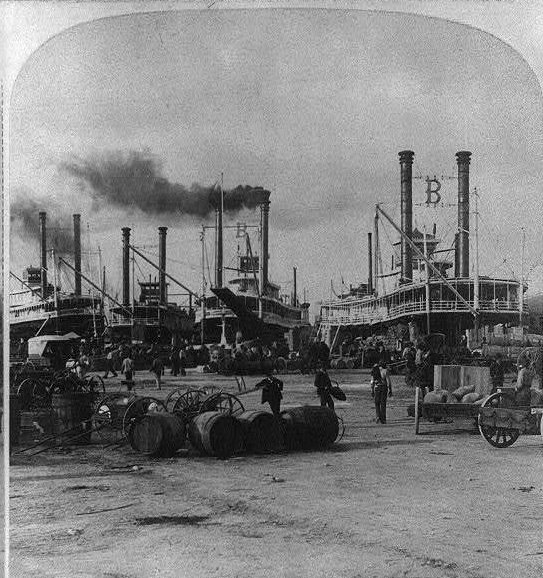

The New Orleans harbor was teeming with every conceivable kind of ship and

boat, and the levee was lined with a forest of sooty cylinders, the huge smokestacks

of docked steamboats. The air seemed

thick with grime. As Paolo debarked he looked back and saw in the shadows

below-decks the immigrants waiting their turn. There, or in a similar space,

stood Regina five years ago, he could just picture her face, eager with hope,

darkened by fear. He tried not to feel guilty that he was a respectable visitor

who didn't have to endure the humiliation of being "processed" as an immigrant. These poor contadini

had to prove that they wouldn't be a "burden to the community," that they were not without prospects, that they

were not idiots, nor carriers of infection, nor banditi. They had to

swear that they were not bound by contract−−with a padrone, say, as his own brothers had

been, back when it was legal. Since he was a gentleman who had actually been

invited to New Orleans, Paolo was not detained. All he had to do was show his

papers and answer a few questions. Although he was born in Sicily, the address

on his passport was Padua, where they could see he was associated with a major

university. They treated him with respect, even sympathy when he told them he

might stay awhile to be with his dying mother.

Mama also thinks Madame Montanet is protecting

her, with silly charms she calls gri-gri, from the evils of this house.

Remember I told you it's supposed to be haunted? Mama has heard noises

on the roof about once a month since we moved here. She's even seen the ghosts of a cruel mistress and her

tortured slave, who somehow managed to break away while being whipped and got

up to the roof, from which she jumped to her death. Her footfalls thump over

the roof once a month. No, not during the full moon, Paolo. (I can just picture

you asking that!) I've heard the noise, but have never seen the

ghost. Mama is sure it was the slave running on the roof, but Mama takes

morphine. Even now during this remission because she says when she doesn't take it she sees the ghosts. Shouldn't it be the other way around? I only hope you

get here before she dies. I'm sure these remissions are only temporary.

"Paolo?"