Graduate Students with the Department

of Biology, University of Louisiana, Lafayette, are supported by fellowships

and teaching assistantships; contact Dr.

Bauer for information.

RECENTLY GRADUTATED STUDENTS:

Jennifer Wortham: Mantis Shrimps (Stomatopods)

Lauren Mathews: Snapping Shrimps

Gregory Hess: Hermit Crabs

Aaron Baldwin: Lysmata Shrimps

Juan Antonio Baeza: Lysmata Hermaphroditism

Jodi Caskey:

Chemical Communication in Shrimps

CURRENT GRADUATE STUDENTS:

Tyler Olivier: River Shrimp Migrations

Sara LaPorte Conner: Shrimp Biology: larvae and parasites

Jennifer

Rasch: Biology of

Processid Shrimps

Jen Wortham: Stomatopod Sexual Biology (Jennifer received a doctoral degree in May '01, and now has an Assistant Professor Position at the University of Tampa)

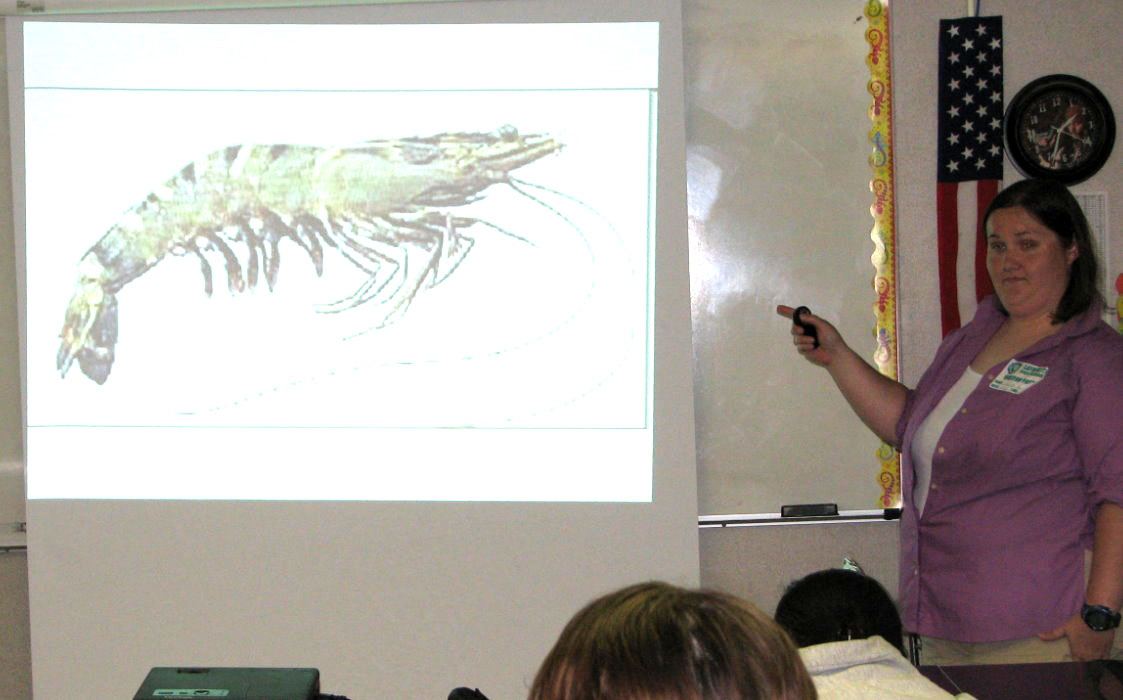

Common Gulf of Mexico stomatopod, Squilla empusa Jen Wortham sorting trawl sample

Stomatopods, with the common name of "mantis shrimps," are common predatory crustaceans in the Gulf of Mexico. They are distinguished a pair of large raptorial appendages, shaped like a jack-knives, which they use in preying on small shrimp and fish, as well as in battles with each other over burrows and mates. Squilla empusa is a "spearer" stomatopod, i.e., its raptorial appendages are used in spearing and slashing prey, rather than smashing them as in another group of stomatopods.

Mantis shrimps have complex courtship and mating behaviors which have been extensively studied in the "smasher" stomatopods. Relatively little study has been done on the sexual biology of Squilla, however, even though it is ecologically important in the Gulf of Mexico and one species, S. mantis, is the target of an important fishery in the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas.

Jen's work deals with the mating system of S. empusa, i.e., the strategies and tactics that have evolved in males and females which promote pairing and mating. What makes a male successful at obtaining and inseminating female? Does a male seek out a female which is ready to mate and then guard her so that he is assured of inseminating (fathering) its offspring? What is the role of female choice in this mating system? Observations of mantis shrimps with time-lapse video, studies on the importance of a burrow as a resource, and studies on the functional morphology of insemination and sperm storage, are being conducted by Jen to answer these questions. This study is supported by observations on basic reproductive biology from specimens collected by Jen on government-sponsored research cruises in the Gulf of Mexico.

Jen presented a paper at the symposium held in honor of Dr. Ray Manning at the May 1999 meetings of The Crustacean Society, held in Lafayette, Louisiana. The presentation was entitled "Internal and external morphology of the stomatopod reproductive system (Stomatopoda: Squillidae)."

Alpheus

armillatus, a "snapping" or "pistol" shrimp from the Gulf of Mexico

Most alpheid shrimps live in male-female pairs in burrows or other shelters which they protect and defend from other members of the same and other species. These burrows, which are usually constructed by the shrimps themselves, are a valuable resource; without them, the shrimps would be easily vulnerable to predators. An important question in evolutionary biology is whether living in male-female pairs is cooperative, i.e., do both the male and female increase the chances that they will successfully reproduce by cooperating in some way? For example, male and female birds nest in pairs because females cannot defend and feed the chicks alone. The male enhances the chances that his offspring will survive to reproduce by cooperating with the female.

In crustaceans, there are many instances in which males are closely associated with females simply so that they will be "in the right place at the right time," i.e., by associating with the female, by protecting and defending her from other males, they will increase the probability that they will inseminate the female when she is receptive. This is called "mate-guarding." It is the male which is forcing the association, without much benefit to the female, who will always find a male ready to mate with her.

In the case of snapping shrimps, Lauren is try to

determine if the male-female association is a cooperative one, with males

helping the female in maintenance and defense of the burrow so offspring

can be produced by the female. Alternately, the male may simply be

serving his own interests, "hoarding" the female so that he will be its

mating partner when she is receptive. Lauren is using techniques

of behavioral ecology, i.e., field studies on population structure, sex

ratio, resource availability, as well as laboratory observations, using

time-lapse video, on agonistic and sexual interactions among individuals.

Lauren Mathews at her field site at the

Smithsonian Linkport facility, Fort Pierce, Florida

Lauren won the "BEST STUDENT PAPER AWARD"at the May 1999 meetings of The Crustacean Society, held in Lafayette, Louisiana, for her presentation "Evolution of social monogamy in snapping shrimp (Alpheidae)."

Clibanarius

vittatus, a common Gulf of Mexico hermit crab

The manner in which male crustaceans pass on their sperm

to females is quite variable. Knowledge about this variability in

the "mechanics" of insemination" is important

in understanding not only the mating strategies of crustaceans but also

their evolutionary ("phylogenetic") relationships. The appendages

and mechanisms used by male hermit crabs are obscured by their shell-living

habits. Greg has made observations and experiments on live hermit

crabs, including matings observed with time-lapse video, as well as observations

on morphology, in order to determine how males pass their peculiar stalked

spermatophores to females. In order to accomplish this, Greg is studying

seasonality of reproduction as well as the relationship of ovarian development

to molting and spawning.

AaronBaldwin

received

a master's degree in 2002, working

on the population biology of Lysmata wurdemanni (Baldwin

and Bauer, 2003), and is now a doctoral student at the

University of Alaska

Aaron Baldwin collecting Lysmata shrimps at night in Pt. Aransas,

Texas

Antonio Baeza: came to ULL with a master's degree from La Universidad del Norte, in Chile, already with several publications on reproduction, symbiosis, and grooming in crustaceans. Antonio graduated with a doctorate in May 2006 and is now a postdoctoral fellow with the Smithsonian's Fort Pierce, Florida, lab and the Tropical Research Institute in Panama. He is now in engaged on research with evolutionary biology of shrimps and other crustaceans with numerous publications in systematics, behavioral ecology, and molecular phylogeny.

Antonio won the BEST PAPER AWARD

at the summer meetings of The Crustacean Society at Williamsburg, Virgina,

2003 for his presentation "Experimental Test of Socially Mediated Sex Change

in a Simultaneous Hermaphrodite, the Shrimp Lysmata wurdemanni (Crustacea:

Caridea)

Antonio Baeza (center) with doctoral advisor Dr. Ray Bauer (left) and Dr.

Martin Thiel (right), Universidad Catolica del Norte, Chile, member of

Antonio's doctoral committee and longtime advisor and collaborator)

Jodi

Caskey: just graduatedafter

completing her dissertation work chemical communication in shrimps.

She has just had two publications accepted from her dissertation (making

a total of 4 from this work) and is now an Assistant Professor at Lane

College in Tennessee.

Current Students:

Sara LaPorte was an undergraduate

research technician (below, left) working on various aspects of data collection

and compilation for the Lysmata Project; she left several years

ago to obtain a master's degree at the University of West Florida in Pensacola

and returned as Sara

LaPorte Conner (below

right, married with one baby girl) and is now is beginning a doctoral program

at ULL in crustacean biology. She is working on the river

shrimp migration study, especially with larval biology and parasites.

Tyler Olivier joined the Bauer Lab in the Fall of 2007 with a SREB fellowship for doctoral studies at ULL. He began immediately to work on the river shrimp migration study and more specifically with the juvenile migration. He presented his work to date at the meetings of The Crustacean Society in Galveston, Texas, in June 2008 (winning the BEST STUDENT PAPER AWARD). He is busily continuing his studies of various aspects of the juvenile migration and its implications for the conservation and restoration of the river shrimp Macrobrachium ohione in the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers.

Tyler Olivier (right) explaining aspects of his work to Louisiana Sea Grant

Director

Chuck Wilson (center) and Dave Nieland (LA Sea Grant manager of research

and planning)

Jennifer Rasch is in her second year of doctoral studies after receiving a master's degree from the University of Masachusetts (Dartmouth). She is has begun work on processid shrimps (Caridea) living in seagrass meadows, with interest in sexual biology, population ecology, and evolution/phylogeny of characters in the family.